Wheeling’s Twentieth Man

“To accept one’s past—one’s history—is not the same thing as drowning in it; it is learning how to use it. An invented past can never be used; it cracks and crumbles under the pressures of life like clay in a season of drought.” ~ James Baldwin

On February 9, 1936, Harry H. Jones, Wheeling’s only practicing African American lawyer at the time, delivered an address over WWVA Radio titled, “Wheeling’s Twentieth Man.”

“About one out of every twenty persons living in Wheeling is of African descent. This twentieth man is not a new comer nor an alien, for his ancestors were settled by force in Virginia one year before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock… Justice and candor require attention to the handicaps suffered by Wheeling’s twentieth man… The group, as a whole, has been barred from employment in our local factories, mills, shops, and stores. The group generally has been restricted to personal and domestic service and coal mining…A reading of the ‘job want’ columns of our local papers will verify this complaint of discrimination. Apparently, the test is COLOR of the worker; not his or her training, experience and character…” [Read the full text of the speech]

Jones went on to describe an entirely distinct black community – one with its own doctors, dentists, restauranteurs, shop keepers, hairdressers, and even funeral directors. Wheeling in 1936 was actually two cities, side-by-side but completely separate. And black people were not welcome in white Wheeling. This was Wheeling under Jim Crow: separate, but decidedly not equal.

Later that same year, Wheeling celebrated its 100th birthday of incorporation as a city with a grand pageant meant to reenact the entirety of its history. Within that pageant and the 112-page program describing it, the only indication that Wheeling’s “twentieth man” had been a part of that history was an A & P Food Store advertisement featuring caricatures of what appear to be black slaves carrying apples, potatoes, and other food as well dressed white men look on, smiling. Black people were otherwise ignored, as if they never existed.

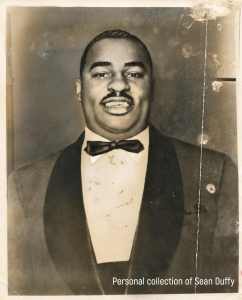

A few months later in December 1936, William Burrus was born on 12th Street. He grew up in this alternate universe, graduated from Lincoln (Wheeling’s black public school), and then, like so many other young African Americans, left Wheeling for Cleveland, where he worked for the U.S. Postal Service and was elected president of the American Postal Workers Union – the first African American to be elected president of any national union by its members.

While visiting his hometown many years later Burrus reflected: “I’ve traveled around the world. I’ve met four presidents…I’ve met Nelson Mandela. I’ve met kings and queens of other countries, and no matter where I went…I was proud to represent that my home was Wheeling, West Virginia. That’s where I was born, that’s where I was raised. That’s the foundation of who I am. I was disappointed that…I don’t think that Wheeling was proud of me.”

So how did this happen? Given Burrus’s disappointment and Jones’s neglected “twentieth man,” how did Wheeling, a northern city that hosted the conventions necessary for the northwestern counties of Virginia to break free from the Confederacy during the Civil War, become so starkly racially divided, just like a city of the old South?

To answer these questions, it is necessary to go all the way back to Wheeling’s founding in 1769, when a white Virginian named Ebenezer Zane made a claim to a narrow strip of land in the valley of the Ohio by carving his initials into a tree, invoking “tomahawk rights.” We now call that land “Wheeling” from the Lenape weelunk, translated as “place of the skull.”

The skull belonged to another white man who arrived prior to Zane, and the Lenape were just one of the indigenous tribes with whom the Zanes and their neighbors would engage in protracted bloody combat to enforce the rights they claimed.

As Wheeling marked the 250th anniversary of Zane’s claim with a citywide observation (this took place in 2019), it became important to acknowledge that people already lived here, just as we remember that other people were brought here against their will.

While discussing plans for this grand 250th observation, Wheeling Mayor Glenn Elliott reminded us to look at Wheeling’s history in a “holistic manner” and “be honest about it … Wheeling was a slave city in a slave state.”

Furthermore, when slavery was abolished after the Civil War, Wheeling became a segregated city in a segregated state. But due to its unique position historically and geographically, Wheeling’s experience with race relations was neither completely northern nor southern. It was both, and neither.

So let’s heed the Mayor’s advice and take an honest, holistic look at the 250 plus-year history of race relations in Wheeling, West Virginia.

Slave City

The truth is that some of the “first families” who joined the Zanes brought with them enslaved human beings with the legal status of property. Wheeling was part of Virginia, the first slave colony, due to the arrival of shackled Africans at Jamestown four hundred years ago in 1619, just as Mr. Jones reminded us. By 1788, the Old Dominion had become the Commonwealth of Virginia, a slave state.

Most of the rest of Virginia’s enslaved population worked on plantations, but Wheeling was different, due to the nature of the economy and a landscape, comprised of a narrow river valley, that did not support large plantations. Here, a much smaller number of slaves were kept as domestic servants or “house slaves” working as carriage drivers, butlers, maids, cooks, or nurses who helped raise children.

The Zanes owned slaves. One, known as “Daddy Sam,” helped the defenders of Fort Henry fight off two sieges by indigenous and British forces in 1777 and 1782. Many of the city’s most prominent families – the Caldwells, Jacobs, Mitchells, Paulls, Paxtons, and Yarnalls – owned slaves. In fact, many streets and even whole neighborhoods are named after slave holders, such as Archibald Woods, for whom Woodsdale is named, the Edgingtons of Edgington Lane, and the Chaplines of Chapline Street. Society hostess Lydia Boggs Shepherd of Shepherd Hall fame, owned as many as 15 slaves.

While the number of slaves owned by Wheeling residents remained comparatively small, the Ohio River, the National Road, and the B. & O. Railroad (both built in part by slave labor), converged to make the city a transportation hub, facilitating a prominent role in the sale of slaves to southern markets, including the Kanawha salt mines, as well as major slave markets further south, such as those in Louisville and New Orleans.

Enslaved people were often marched along National Road, chained together in “coffles,” toward the market house on 10th Street, where they were auctioned to the highest bidder, like cattle. The Mansion Museum at Oglebay Park still has the bell that was rung to call people to these slave auctions.

In a 1907 book called Bonnie Belmont: A historical romance of the days of slavery and the Civil War, John Salisbury Cochran, an Ohio Civil War veteran, judge, and eyewitness to the Wheeling slave auction block, described it this way:

“The auction block was on the west side of the upper end of the market about where the city scales are now located. It was a wooden movable platform about two and a half feet high and six feet square approached by some three or four steps.”

In Cochran’s story, a Quaker named Joshua Cope purchases the slave named Aunt Tilda Taylor, and sets her free. The Quakers were abolitionists, and operated the Underground Railroad just across the Ohio River from Wheeling, helping slaves escape to freedom.

Another Quaker from Mt. Pleasant Ohio, Benjamin Lundy, became a staunch abolitionist after witnessing a slave auction in Wheeling. Lundy wrote about seeing “droves of a dozen or twenty ragged men, chained together and driven through the streets, bare-headed and bare-footed, in mud and snow, by the remorseless ‘SOUL SELLERS,’ with horsewhips and bludgeons in their hands!”

According to Lincoln School teacher Mrs. Dorothy Cooper, “… at the corner of 11th and Chapline Streets, a whipping post stood. Squire McConnell had charge of this and administered punishment to all slaves who had committed offenses.”

Moreover, city and county codes often made participation in “slave patrols” mandatory for white people, even those who did not own slaves. This policy, designed, among other things, to snare escaping slaves and suppress any kind of uprising, was enforced as a “civic duty.” Some scholars argue that the idea of whites “policing” former slaves has influenced modern law enforcement.

In any event, by 1860, when Wheeling’s population was 14,100 people, there were 100 enslaved people in Ohio County – 42 men and 58 women. One of those, Sara “Lucy” Bagby, escaped from Wheeling, and with the help of the Underground Railroad, fled to Cleveland. Her “owner,” William Goshorn, found Lucy and had her returned to Wheeling under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, making her one of the last “fugitive slaves” to be returned to her owner prior to the Civil War. During the war, Lucy was freed by a Union officer even as Goshorn was arrested as a traitor.

Yet, West Virginia’s history text books have often distorted the essential truth of slavery in what became West Virginia. (see Wood, V., West Virginia: 150 years of statehood, wherein, “…westerners claimed slavery went against the spirit of the Declaration of Independence…”)

Statehood & Emancipation

After a series of conventions held in Wheeling, on June 20, 1863, West Virginia broke from Virginia and became the only state to be born of the Civil War. Wheeling was the birthplace of West Virginia. But secession from secession was based on pragmatic, mostly economic concerns, rather than abolitionist sentiment. In fact, the reluctance to let go of slavery proved a major sticking point for statehood delegates.

Despite the efforts of the few abolitionist delegates like Wheeling minister Gordon Battelle, whose attempt to abolish slavery in the state’s new constitution failed, in most ways, the attitudes of western Virginians toward slavery were indistinguishable from those held by the rest of Virginia. This is made clear by the proslavery attitudes of many leading unionists like Restored Government of Virginia Senator John Carlile, a slave owner himself, who, even as Congress and President Lincoln pressured statehood delegates to do something about the peculiar institution, wrote “I believe that slavery is a social, political and religious blessing.”

In response to Lincoln’s pressure, Restored Government of Virginia Senator Waitman T. Willey introduced a gradual emancipation amendment, which said slaves under 21 years of age on July 4, 1863, would be free upon reaching that age. Willey’s proposal was successful, and the new state of West Virginia was born with 18,000 human beings still enslaved within its borders.

Meanwhile, on January 1, 1863 (after having approved West Virginia’s statehood bill the evening prior), Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. By recognizing that it was about freedom, Lincoln’s proclamation finally gave meaning and purpose to the horrific war that would take more than 600,000 American lives. But the proclamation only applied to states in rebellion, meaning it specifically did not apply to the counties that would become new state of West Virginia that June.

Nevertheless, the African American people of Wheeling would celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation for decades after the war ended. Wheeling hosted elaborate Emancipation Day celebrations. Thousands of mostly African American people thronged the town for parades, gatherings at the State Fair Grounds on Wheeling Island, music, banquets, and speeches by dignitaries, including, in 1891, America’s second black Senator, Blanche K. Bruce.

Reconstruction

The Reconstruction Amendments – the 13th, which ended slavery, the 14th, which made ex-slaves U.S. citizens, and the 15th, which extended suffrage to black men – were all ratified by the new state of West Virginia in Wheeling’s Linsly Academy building on Eoff Street, the temporary home for the new state’s government now known at the “First State Capitol.”

Despite the Thirteenth Amendment, in many ways, slavery did not end in the former Confederacy. The text reads: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” States in the Old South soon took advantage of the second clause to developing a corrupt system to replace slavery with convict labor. African American prisoners were leased to private parties, providing cheap labor and creating an incentive to imprison even more black men, often on trumped up charges.

Even for those freedmen who fled north to escape the convict lease system and other horrors, West Virginia proved no safe haven. Despite the end of slavery, blacks in West Virginia still could not vote, serve on juries, or hold public office.

The northern city of Wheeling was also unsafe. On February 1, 1866, the city’s Democratic newspaper, the Wheeling Register, opined: “We are opposed to extending suffrage to colored persons in this state.” Yet, after the 1870 ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, hopes for black suffrage ran high in Wheeling as the mayor joined the city’s African Americans in a parade. A banner with the words “Freedom – it is an honor to be freemen,” was carried through the streets of town.

Still, West Virginia’s Reconstruction experience was quite different from that of the defeated Confederate states. While the defeated Confederate states faced “bayonet rule,” during Reconstruction, federal troops were not sent to West Virginia (a loyal Union state) to enforce black civil rights. About a quarter of the state’s white population were disenfranchised due to Confederate loyalties. African American suffrage gave the latter leverage, rendering blacks pawns in the struggle between liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats for political power.

West Virginia’s conservative Democrats, who seized power in 1872, would leverage the black vote to re-enfranchise former Confederates. If former black slaves were to vote, the reasoning went, how could white former Confederates be prevented from doing the same?

In 1870 and 1871, the U.S. Congress passed the Enforcement Acts, which imposed fines and imprisonment against all attempts to “hinder, delay or obstruct the exercise of the franchise by the Negro or with counting votes cast by them.”

Conservative Democrat “Redeemers” (“redemption” defined as taking political power back from the Radical Republicans and black freedmen) would leverage the Enforcement Acts as a way to re-enfranchise white Confederate voters and effectively take control of state politics. They found ways to circumvent the Enforcement Acts, disenfranchising blacks without directly forbidding them to vote.

In summer 1870, delegates met in Parkersburg to settle the suffrage issue, with conservative Democrats insisting that white ex-rebels must be re-enfranchised in light of black suffrage. The twenty black Republican delegates who attended were not permitted to stay in local hotels and some had to find lodging across the river in Ohio.

During the 1870 election Democrats pressured registrars to register ex-Confederates along with African Americans. The re-enfranchisement of nearly ¼ of the state’s white voters in this way resulted in a sweeping victory for the Democrats in the 1870 election. Conservative Republicans joined with Democrats, leading to approval of the Flick Amendment, which enfranchised former Confederates by 1872.

That same year, a Wheeling carpenter and former slave named Taylor Strauder murdered his wife with a hatchet. Strauder was convicted by an all-white jury and sentenced to hang. His attorneys challenged the state law limiting jury service to white males as a violation of the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment. When the case reached them in 1880, the U.S. Supreme Court concurred, holding in Strauder vs. West Virginia that the law was “a brand upon [African Americans]…an assertion of their inferiority, and a stimulant to that race prejudice which is an impediment to securing to individuals of the race that equal justice which the law aims to secure to all others.’’

Despite this progress, nationally, northern interest in enforcement waned as southern whites were relentless in their attempts to reestablish white supremacy and terrorize blacks into submission through the use of Jim Crow segregation, Black Codes, the convict lease labor system, the erection of Confederate monuments, the violence of the KKK, and lynching.

To the extent that any of these tactics existed in West Virginia, they were less virulent. The KKK was active in the state, and even in Wheeling. But while 3,446 lynchings of African Americans occurred nationwide between 1882 and 1968, according to the Equal Justice Initiative 35 occurred in West Virginia during the same period, with none of these in Wheeling. By 1921, the state had passed an anti-lynching law.

But racism in Wheeling, as elsewhere in the state, remained systemic and its practitioners unabashed.

Lincoln School

Drafted by newly empowered Democrats, West Virginia’s 1872 constitution included Article XII, Section 8, which decreed, “White and colored persons shall not be taught in the same school.” This language would remain in the state’s constitution until 1994, and even then, 42% of the state’s population voted to keep it.

Lincoln, Wheeling’s school for African Americans students, was founded in 1866 in a two-room house on 12th Street. In 1875, it moved to the black neighborhood at 10th and Chapline.

Lincoln’s most celebrated principal, James McHenry Jones, arrived in 1882. Jones would publish a novel called Hearts of Gold, which highlighted important issues like racism, segregated education, lynching, and convict labor. Jones left Lincoln in 1900 to serve as president of the West Virginia Colored Institute, now known as West Virginia State University.

Even after Jones’s tenure, the academic performance of Lincoln’s students remained first rate. In its August 1916 issue, The Crisis magazine (edited by W.E.B. Du Bois), wrote: “The pupils of the Lincoln School at Wheeling, W. Va., in a recent test, outranked the ten white schools in spelling.”

The school Jones helped build became a source of pride in the black community, but as a public facility, it remained underfunded and inadequate.

Born in Wheeling in 1936, William Burrus graduated from Lincoln in 1954 as part of the last class before the U. S. Supreme Court decided Brown vs. Board of Education, the landmark school desegregation case. Burrus had transferred from Blessed Martin, Wheeling’s segregated Catholic high school, so that he could play football at Lincoln.

“Once a year, our coach, Mr. Kinney, would take us to Wheeling High after hours, after all the kids were gone,” Burrus recalled during a 2015 interview. “It was in the dark. And they would permit us to go through their used equipment, and we would take that back to Lincoln…They would bring us in there after the school was closed so they wouldn’t see us. And that was so very, very demeaning. I mean, you can imagine, a 15, 16-year-old kid sneaking in, with his coach, into the bowels of the high school…and we all remembered that. That’s where we got our football equipment from.”

Ann Thomas (who would become Wheeling’s first black nurse) was still attending Lincoln when the Brown decision was announced. She said that Principal Phillip Reed held an assembly to let students know about the Brown decision. “My life changed,” she recalled. “My parents felt like this was a dream come true… So I took that opportunity – hesitantly – but I ended up graduating from Wheeling High. And I was one of the first blacks to attend Wheeling High.”

The Brown case was the beginning of the end for segregated schools, but it was by no means the end of Jim Crow.

Jim Crow

“Jim Crow” was a term that emerged from a minstrel song. Minstrel shows were musical comedy plays, in which white performers wore blackface to mock African Americans. They were quite popular in Wheeling, where fraternal organizations, churches, and high schools organized blackface minstrel shows well into the 1970s.

When Jim Crow laws were challenged in the late nineteenth century, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Plessy vs. Ferguson (1896) that such laws were constitutional, so long as public facilities were “separate but equal.” Of course, the reality was that separate facilities for African Americans, such as Wheeling’s Lincoln School, were underfunded and inferior in quality.

In addition to the school segregation in the state’s 1872 constitution, West Virginia had laws against blacks serving on juries (overturned in the Strauder case – see above), and an anti-miscegenation statute that made it illegal for blacks and whites to intermarry (overturned by Loving v. Virginia, 1967). According to one source, “In a 1954 questionnaire issued to states by the U.S. Supreme Court in preparing its Brown v. Board of Education decision, West Virginia noted that the state ‘has no ‘Jim Crow’ laws, and we are not aware of any such prior laws in the statutes. The prevailing custom throughout this State has been and continues to be the catering to caucasians only for the purpose of lodging, public institutions, public halls and restaurants.”

Whether by code or custom, for African American people in Wheeling, Jim Crow meant separate everything—from restaurants and movie theaters to beauty parlors and hotels. Even when celebrities like world heavyweight boxing champion, Joe Louis, visited town, they could not stay in white-only hotels. There was a separate branch of the YWCA, the “Blue Triangle” and a separate library on 12th Street. Many Wheeling businesses were listed in the Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide for African American travelers to hotels, restaurants, and other public facilities where they could be served and not experience the embarrassment of being told they weren’t welcome.

William Burrus recalled working with his uncle who shined shoes at the McLure Hotel. “They had colored restrooms. And I was about twelve years old I guess, and it was so demeaning to me that here I was forced in the hotel to assist my Uncle in shining shoes and I couldn’t even use the restroom.” He also remembered “Colored Only” signs on the water fountains. “And we were close enough to Ohio and Pennsylvania where they did not have those Jim Crow laws. I could see and feel the differences that were imposed upon me because of the color of my skin.”

Ann Thomas met her future husband, Clyde, at the skating rink at the Market Auditorium, the building that replaced the old market house where slaves and once been bought and sold in Wheeling. African American kids could only skate on Monday nights. Clyde, who grew up without Jim Crow across the river in Bellaire, Ohio, became a football star for the semi-pro Wheeling Ironmen as well as the first (and still the only) African American to be elected to Wheeling’s City Council.

While the black population of West Virginia as a whole dropped significantly just after the Civil War, it grew in Wheeling. With the full effect of the Great Migration (during which some six million African Americans left the old south for opportunity and greater freedom), the state’s black population grew during and after WWI, primarily due to the lure of jobs in the southern coalfields and northern factories. Though remaining relatively small, Wheeling’s black population doubled between 1900 and 1930.

Despite the outmigration fueled by Jim Crow, the Great Migration brought diversity, and Wheeling’s African American community thrived, producing many entrepreneurs, professionals, and cultural leaders.

Examples include Leon “Chu” Berry (1908-1941), a legendary saxophone player who performed with the likes of Billie Holliday, Count Bassie and Cab Calloway; Everett Lee (1916- ), who learned to play violin on Wheeling Island and became the first African American to conduct a major symphony orchestra in the south; bass guitarist Billy Cox (1939- ), who performed with Jimi Hendrix; and beloved community leader James S. “Doc” White (1901-1988), whose Northside Pharmacy became a safe gathering place for generations of African American young people.

Civil Rights, Redlining, and Urban Renewal

As Jim Crow was on the way out in Wheeling and elsewhere, the modern Civil Rights struggle was heating up in the 1960s and 1970s.

Diana Bell, an Ohioan who moved to Wheeling when she was twelve, offered a different perspective. “Ohio was a totally different climate,” she explained. “And it’s still different to this day…I never had the racial tension that I had here…That little line made a big difference.”

Young Diana experienced Wheeling as a hub of Civil Rights activities. She remembered demonstrating with groups at city hall. She also remembered rioting and vandalism when Dr. King was assassinated. “We had to write ‘Soul Sisters’ on our house,” she recalled, “’Soul Brothers’…so that people would know that someone black lived there, so they wouldn’t do anything to our house.”

In post Jim Crow Wheeling, African Americans were further disadvantaged by exclusionary zoning regulations that restricted where they could live. When this was made illegal by the 1917 Supreme Court decision Buchanan v. Warley, racially restrictive covenants in real estate contracts followed (see Kammer, B. “How I Benefitted from White Supremacy Growing Up in Wheeling, West Virginia”).

When those covenants failed, white people simply left, a phenomenon known as “white flight,” and the neighborhoods where blacks were thought to be too numerous were “redlined,” appearing on “residential security” maps to warn white investors away. African Americans also faced blatant discrimination when seeking credit, both for home and business loans.

When these detriments are added together, the terms “white supremacy” and “white privilege” gain context and meaning.

The 1970s also brought “Urban Renewal” to Wheeling. This effort to redevelop “blighted” areas of town had its greatest impact on traditionally African American neighborhoods, that is, those that were redlined.

During Clyde Thomas’s tenure as a councilman in the mid-1970s, Wheeling’s City Council considered urban renewal for the primary African American neighborhood, the 1100 block of Chapline Street. An earlier version had essentially pushed established African American communities out of South and Center Wheeling.

When a young man questioned Clyde’s presence on Wheeling’s urban renewal committee, Clyde responded by saying, “Somebody needs to be there that looks like me, who can hear, who can read, who can comprehend and find out what it is they want to do with our community, because our community is going to be impacted by this urban renewal.”

And the community was impacted, heavily. The black-owned businesses and residences on Chapline Street between Lincoln School and 12th Street were taken through eminent domain and razed.

“The whole African American social fabric was there on Chapline Street,” Ann Thomas recalled. “When urban renewal did happen, people got displaced. Some people went to Ohio. It pretty much decimated the black community. The black community from that point, has never been the same and will never be the same.”

Epilogue

From major slave market to segregated city, Wheeling maintained a southern attitude toward African Americans for most of its 250-year history. Though it served as the seat of secession from secession during the Civil War, and though after the war its treatment of freedmen did not approach the level of cruelty of the old Confederacy, it maintained its custom of treating blacks as second class citizens, separating them from whites, creating a hidden subculture not unlike other northern cities that took an out of sight, out of mind approach to race relations. Shunned and ignored, African Americans created their own separate Wheeling with its own vibrant culture.

This neglectful past has heavily impacted the present. Wheeling continues to struggle to create an integrated, diverse community. Part of that struggle has to include remembering and honoring those who persevered and achieved despite that neglect.

Though he did not live to enjoy the accolades (he died in May 2018), William Burrus was inducted into the Wheeling Hall of Fame, along with Everett Lee, this past summer. Despite his disappointment, Wheeling is indeed proud of William Burrus.

Ann Thomas, who chose to stay in Wheeling, passed in February 2019 with her dream for her husband Clyde to also be enshrined in the Wheeling Hall of Fame unfulfilled.

More to come in PART 2…

Note

This research was adapted into a multimedia program for the Ohio County Public Library’s Lunch With Books Series. YWCA Diversity and Outreach Director, Ron Scott, Jr., presented the program for Black History Month. The resulting presentation weaved photographs, videos, and primary source material into a 250-year story of African American life in Wheeling. Taken on the road to a local high school and middle school, the program was experienced by more than 500 students.

For a powerful look at how this history has affected contemporary, that is, post-“Jim Crow,” times, see Brian Kammer’s remarkable essay, “How I Benefitted from White Supremacy Growing Up in Wheeling, West Virginia.”

Sources

Archibald Woods Papers, College of William and Mary. https://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=wm/viw00093.xml. (slavery letters, ads, and other documents).

Bell, D. In-person interview. 2012.

Burrus, W. In-person interview. Feb. 2015.

Cochran, J.S. Bonnie Belmont: A historical romance of the days of slavery and the Civil War. 1907.

The Crisis magazine (edited by W.E.B. Du Bois), August 1916, Vol. 12, No. 4, P. 95.

Dunaway, W. The African-American Family in Slavery and Emancipation. 2003.

Equal Justice Initiative. https://eji.org.

Foner, E. The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution. 2019.

Gates, H.L. Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow. 2019.

Hadden, S. Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas. 2003.

Hansen. C. “Slave Patrols: An Early Form of American Policing.” lawenforcementmuseum.org/2019/07/10/slave-patrols-an-early-form-of-american-policing/.

Inscoe, J.C. Appalachians and Race: The Mountain South from Slavery to Segregation. 2005.

Jones, H.H. “Wheeling’s Twentieth Man,” WWVA Radio speech. Feb. 9, 1936. YWCA Collection, OCPL Archives.

Link, W., Roots of Secession, Slavery and Politics in Antebellum Virginia. Univ. of North Carolina Press. 2003. pgs. 151–152

North-Western Virginia Gazette. 1820. (slavery ads).

Thomas, A. In-person interview. Feb. 3, 2015.

WV Dept. of Arts, Culture, & History. West Virginia Archives and History. http://www.wvculture.org/history/archivesindex.aspx.

West Virginia Encyclopedia, e-WV. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org.

Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. Various dates.

Wheeling Register. Various dates.

YWCA Collection (and Blue Triangle Collection). OCPL Archives.

Do you have any information on the Hamlins of Wheeling? They were both professionals.. Doctor and Dentist

Thank you

I have heard of them many times. They were always mentioned in interviews. I wish we had more information. Please let us know what you find.

What a great essay: well written and beautifully illustrated. I missed the article in Goldenseal last year and was grateful to find it here. Always more to learn. Looking forward to the 2nd part.

Thank you Dan.

In the late fall of 2019 .. I was returning to Canada from Texas and drove across the bridge from Ohio to the Wheeling Tunnel. As I looked down at the town of Wheeling WV … I was struck by how quaint it appeared. I made the time to drive around the town for about 30 minutes. It has remained in my memory ever since.

It is compelling to read of the racial history of this small town. As I attended University in the USA, I am well aware of the history of slavery, the civil war, reconstruction, Plessy vs Ferguson, Jim crow, race relations since.

As an outside and educated observor of a country that I have long admired. It saddens me that 165 years after the Civil War … white privledge, white supremacy and the diminishment of black people still goes on.

Thanks for this eloquent comment Steve. It saddens me too.

Hello, my Great-Great Grandmother is Dorothy Cooper however I can’t seem to find a picture of her if anybody has information contact me please

I was born in Wheeling West Virginia one December 19, 1962, I was raised across the river in a very small town called Maynard/ Saint Clairsville, Ohio just 9 miles from Wheeling , I cant begin to count the number of times I walked across the bridge from Bllair to Wheeling, I never knew the history of slavery in Wheeling , nor anywhere about the Jim Crow area of Wheeling, I knew the my parents protested for equal rights, I knew that my ancestors were abolitionistas in Mount Pleasant, and Harisville ,Ohio. In Harision county, one of the lady’s who were enslaved stayed with my 3rd. Great grandparents, and did so her children and grandchildren, my 2ed.great Aunt Bertha Harris who lived in Saint Clairsville after marrying a man from Wheeling, they raised their family there, the former enslaved girl who chose to stay with my third great grandparents instead of heading further northward, her name was Lucille , my grandmother was named after her. None of this was taught in school growing up, I feel lied to, and sick inside, knowing all this history took place only 9 miles from were I grew up

Sincerely

Myra Moore