Springtime in Wheeling

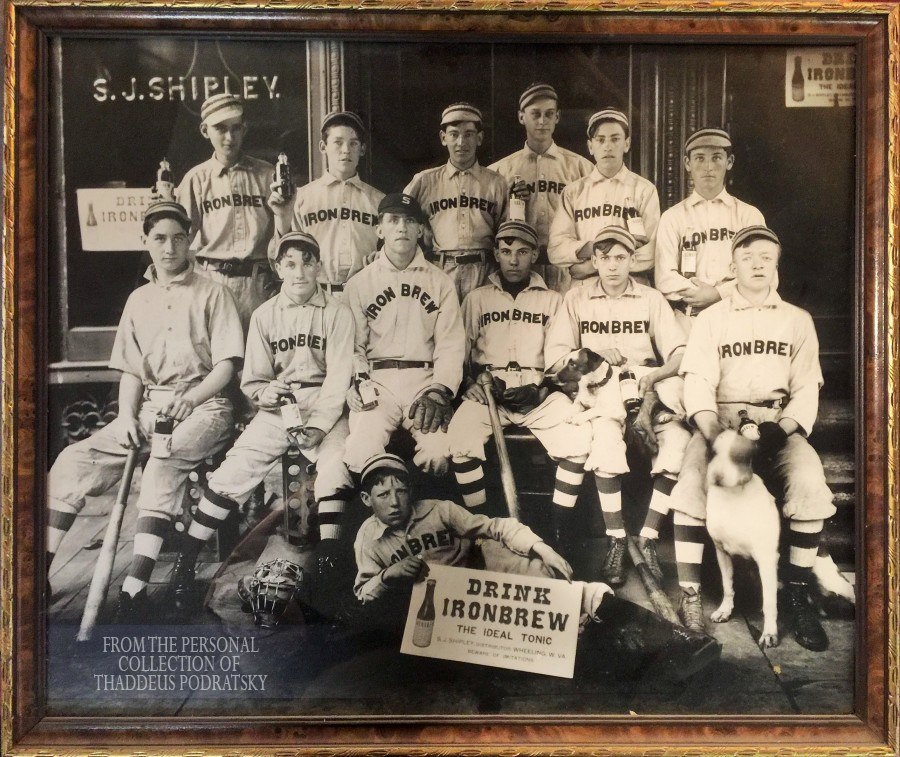

Nothing says spring quite so clearly as an April day at the old ballpark, with the sun shining warmly on your face and tiny, cool bubbles bursting on the tip of your nose as you raise an ice cold bottle of sweet soda pop to your lips for a refreshing drink. Well, that’s our theory anyway, as we celebrate spring with a new exhibit of baseball artifacts combined with Thad Podratsky’s amazing collection of early Wheeling pop bottles — on display now at the Ohio County Public Library. As a complement to this display, we present a two-part post on the history of baseball and pop bottling in old Wheeling.

Part 1: “A Social Game of Ball”

“Ray, people will come Ray … They’ll arrive at your door as innocent as children, longing for the past … And they’ll walk out to the bleachers; sit in shirtsleeves on a perfect afternoon. They’ll find they have reserved seats somewhere along one of the baselines, where they sat when they were children and cheered their heroes. And they’ll watch the game and it’ll be as if they dipped themselves in magic waters. The memories will be so thick they’ll have to brush them away from their faces. People will come Ray. The one constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It has been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt and erased again. But baseball has marked the time. This field, this game: it’s a part of our past, Ray. It reminds of us of all that once was good and it could be again. Oh… people will come Ray. People will most definitely come.” -Terence Mann [James Earl Jones] in Field of Dreams

“Wheeling’s a swell town to play [baseball] in. The fans here like a good game an’ don’t care who wins. The kids are bad, though!”

–from The Short Stop (1909) by Zane Grey, writer and baseball player

During the Civil War, Wheeling served as the birthplace of the new state of West Virginia. In the years immediately after the war ended, Wheeling would serve as the birthplace, in the new state, of a new game called “base ball.”

In August 1866, Wheeling’s Jacob Hornbrook became the first West Virginian to play organized baseball when he went to bat for the Hunkidori Base Ball Club on Wheeling Island Commons. In this, their first real “match game” against the more established Union Base Ball Club of Washington, Pennsylvania, the Hunkidoris lost by the absurdly lopsided score of 45-12. Yet after the game, the opposing “baseballists” gathered sportingly for some first class socializing, including dinner and drinks, toasting, speeches, and general merriment.

The Hunkidori Club was organized by a Civil War veteran, and most of the club’s members were veterans. And with names like Hornbrook, Hubbard, and Lukins, most went on to achieve success as business and social leaders in town. Early base ball was a gentleman’s game. It was also an urban rather than a rural game, and in the years that followed, the rapidly industrializing “Nail City” would play an important and vibrant regional role in the development of the game into a national obsession.

By 1868-69, baseball’s popularity as a spectator sport in Wheeling had grown exponentially as more than two-dozen teams represented the city and towns just across the river in Ohio. These included clubs with names like Baltic, Star, Anchor, Resolute, United, LaBelle, Eagle, Muscle, Bachelors, Belmont, Osceoloa, and Benedicts.

In time, the game became more democratic, with more working class men from the ranks of the steel and iron-workers, the tobaccos workers, factory laborers, and the volunteer firefighters participating and dominating the play. Some played for neighborhood teams, such as the North Wheeling Champions and Crescents, the Nationals of Wheeling Island, the East Wheeling Velocipedes, the Centre Wheeling Atlantics, and the South Wheeling Uniteds. Others were sponsored by local businesses.

Emerging from this cacophony as the elite team was the Baltic, composed largely of men of Irish working class heritage, which played its games at the Fair Grounds on Wheeling Island. The Baltics defeated the Uniteds to claim the first West Virginia championship in 1868 and to open the 1869 season, met the mighty and ballyhooed Red Stockings of Cincinnati, the first true professional baseball team. An unprecedented crowd of 1000 people descended upon the ballpark at the Fair Grounds to witness the spectacle. But the game was called after just three innings with the score Red Stockings 44, Baltics 0.

By the 1870s, the best Wheeling teams were the Nail City Club and the Standards (sponsored by Standard Publishing). The Standards signed a local phenom, 15-year-old shortstop John Wesley “Pebbly Jack” Glasscock, who would become the first West Virginian to play in the major leagues, where he lasted 17 years.

In 1886, a team from Bellaire known as the Globes began to dominate local baseball. The team’s star player was an African American man named Solomon “Sol” White, a highly regarded sandlot player from Bellaire, OH, who later distinguished himself as a player, manager, and executive in the Negro Baseball Leagues. The author of “Sol White’s History of Colored Baseball,” he lived long enough to see the color barrier broken by Jackie Robinson (see also).

By 1887, the Wheeling Base Ball Association merged the Globes with another club to form a semi-pro Wheeling squad known as the “Nailers.” They had a true baseball park with grandstand constructed on Wheeling Island near the location of the current stadium. Over the four years of the team’s existence, an impressive total of nineteen players left the Nailers for the major leagues, including future major league hall-of-famer Edward “Big Ed” Delahanty, who batted .408. Playing home games on a diamond built by beer baron Henry Schmulbach on his Wheeling Island farm, the Nailers won an Iron and Oil League pennant (Wheeling’s first significant championship) in 1895 with the help of local boy Jack Glasscock, who had returned to play for his hometown team in the twilight of his career. That same year, hometown boy Jesse “Crab” Burkett, who was was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1946, won a major league batting title, hitting .405 for the Cleveland Spiders of the National League. Baseball’s popularity in Wheeling was skyrocketing.

Amateur baseball was also growing in popularity, with neighborhood teams and company teams sporting evocative team names such as the Pike Street Sluggers, Twenty-Fifth Street Stars, Tobacco Chewers, Wheeling Laundry, Little Havana, Stephens Blue Seals, Lutz Brothers Tobacco, Modern Sluggers, Kindelberger, Barn Doors, Married Men, and Pink Garters. They played on fields at Tunnel green, 41st Street Grounds, B&O Grounds and Island Park. A team would often throw down a challenge to another team to meet them at a certain field on a certain day. A wager was usually involved.

In 1900, the Elm Grove-based Wheeling Athletic Club sponsored a pro team known alternately as the Nailers or the Stogies. Home games were played on Wheeling Island with star players like Bill “Bunk” Congalton, and pitchers John Skopec and Ed Poole. Sunday games were against the law back then, but seeing the profit potential, team owners pushed the envelope. When police tried to break up a 1900 Sunday game on the Island in the grandstands emptied and a riot ensued. But the law stood, and Sunday baseball in Wheeling did not achieve viability until the 1920s.

In 1901, the new Wheeling Stogies started playing Sunday baseball on the field at Sisters Island Park, on the small Ohio River Island off north Warwood (accessible at the time only by steamboat), that would later house the short-lived Coney Island Amusement Park. But the absurdly short right field and small attendance rendered the arrangement unsustainable.

By 1903, the Stogies joined the Central League, where they would remain until the First World War. Their star players at the time were the big, strong and athletic outfielder Gene Curtis, pitcher Walt Miller, and the hard drinking clown prince pitcher Bill “Brickyard” Kennedy. The Stogies won pennants in 1905 and 1909. In the “Dead Ball Era” (1905-1920), when pitchers dominated hitters, the Stogies sent two of the best hurlers to the mound: Bill Friel and Nick Maddox, who moved on to win 23 games (including a World Series game) for the Pirates in 1909.

A few years after the Great War ended, the Stogies were reborn in the new Middle Atlantic League, which thrived from 1925 until the Second World War. It was during this period that future Pittsburgh Steelers founder Art Rooney would play for the Stogies along with his brother Dan. Both were capable hitters and beloved characters. Art was a centerfielder who batted .369 in 1925 (second best in the whole league) and Dan, who later became a Franciscan friar, played catcher. While playing for Wheeling, the Rooney brothers took on a whole baseball squad (or as many of them as they could get their hands on) when players from a Frostburg Maryland team taunted them with anti-Catholic jibes.

Other notable players of the era included Bill Prysock, hitters Gerald “Gee” Walker, Frankie “Dollie” Doljack, and Bill Prichard, as well as pitchers Bill Gwathmey and Billy Thomas. The Stogies played the first night game under lights for the MAL in 1930 under owner Charles Holloway, but it wasn’t enough to save the beleaguered franchise, which folded in 1932. In 1933, the Stogies were revived by the New York Yankees and George Weiss. The team went on to win a pennant with six future major league players on its roster, including batters John Aloysius “Buddy” Hackett and Jimmy Hitchcock, and ace pitchers Kemp Wicker and Joe Vitelli. But the 1934 team was as dismal as the 33 team was good, and Weiss moved the franchise to Akron.

Wheeling, the birthplace of baseball in the Mountain State, had lost its storied professional team.

While it was the end of the era of old-time baseball it was by no means the end of baseball in Wheeling. The Wheeling Twilight League continued the semi-pro tradition. All-American Girls Professional Baseball League star Rose “Rosie Gaspipe” Gacioch honed her craft at Pulaski Field in South Wheeling. Wheeling Post 1 advanced to the 1949 American Legion World Series. Little league, high school, and college baseball thrived. Major League journeymen George (b. 1926) and Gene Freese (b. 1934) learned baseball in the sandlots of Wheeling, while future Hall of Famer Bill Mazeroski was born at Wheeling Hospital in 1936. Led by Blaine Ohio pitcher Joe Niekro, West Liberty College won an NAIA baseball national championship in 1964. Joe and his brother Phil went on to win 549 major league games, the most by any pair of brothers in history.

Wheeling’s legacy as the birthplace of the game of baseball in the state of West Virginia was secure in the gnarled and capable hands of these and many other baseball legends.

Please stay tuned for Part 2 of Baseball & Soda Pop: Springtime in Wheeling, which will explore the history of soft drink production and bottling in the Nail City.

Sources

West Virginia Baseball: A History, 1865-2000 by William E. Akin (McFarland & Co., 2006)

Wheeling Daily Intelligencer and Wheeling Intelligencer, various editions, 1866-1934

Wheeling Register and Wheeling News-Register, various editions, 1866-1934

Great article on baseball..

I was born in Wheeling at the Ohio Valley Hospital. Stayed for 20 years when I entered the military. Played little league baseball for center wheeling Red Sox. My older brother played for the Cave Club league. I never knew the history of what I just read, especially about the Rooney brothers. What a great article. I thank you for the wonderful information.