Memories of Wheeling Downs & Big Bill Lias

by Hugh Stobbs

[This story is in partnership with our friends at Weelunk. Be sure to read about Steve Novotney’s interview with Mr. Stobbs, here.]

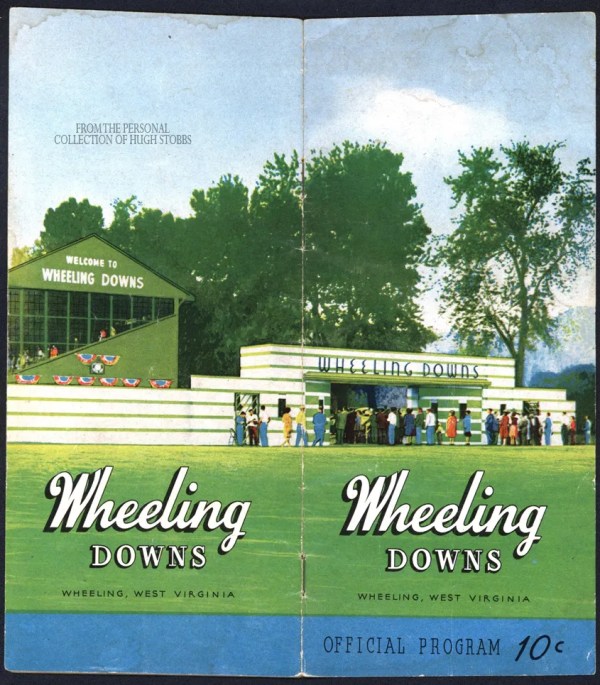

[Hugh Stobbs, who worked for many years at Wheeling Downs, appeared at Lunch With Books at the Ohio County Public Library on July 26, 2011 to discuss his memories of the track, the horses, the gamblers, Bill Lias and all of the things that made Wheeling Downs the interesting place it was in its heyday. The following story was adapted from the transcript of his program as well as from recent discussions with Mr. Stobbs. Pieces from Mr. Stobbs’s extensive collection of Wheeling Downs memorabilia are currently on display in the store windows at 1310 Market Street in downtown Wheeling and in the main display are at the library.]

This talk will be presented in three segments. The first will explain how Wheeling Downs developed through the years. The second will be about Bill Lias, because everybody associates him with Wheeling Downs. And the last segment will cover my introduction to Wheeling Downs, the different jobs I did there, the people I worked with, and various other things about the track.

Early Horse Racing in Wheeling

I’d like to start back in 1769 – the Zane brothers came to the area and they made a fortune in land speculation. Ebenezer Zane laid out the original 112 lots that now constitute downtown Wheeling. The Zane brothers bought Wheeling Island from an Indian chief whose name was Cornplanter for a barrel of whiskey and an old iron chisel. He got a pretty good deal there.

The earliest settlers raced around the prehistoric burial grounds that were around town. The first track specifically built for horse racing was in Beech Bottom in 1806 on a farm. The Virginia Horse Racing Club rented the track each fall. By 1825, Echols Field in the area known as Ritchie (South Wheeling) featured a four-mile track. Echols Field closed in 1832 because of the city expansion. The next track was on John Good’s Farm at the base of Chicken-Neck Hill. It closed after a couple of years because the owners lost money. A fourth track opened in 1839 was closed shortly after because of the rampant fights that occurred at the races.

A Brief History of Wheeling Downs

One of the early guys who got racing started in Wheeling was brewery owner Henry Schmulbach. He bought a whole track of land out in Mozart and he put in his own casino and a dance floor. He also had an inclined cable car that went up the hill, just like the one in Pittsburgh. Then he bought land on the north end of the Island and put in his own horse race training facility. He built a great big barn, and it was a quarter of a mile track. And he had a lot of people working there. He also had apprenticeships for jockeys and trainers and others, so they could learn the trade.

But because of the depression [of 1893], Schmulbach got out of the horse racing business, and that’s where the West Virginia State Fair came in. The West Virginia State Fair began on Wheeling Island in 1881 and lasted until 1930. A grandstand was built there in 1895 along with the track itself. The State Fair eventually went into receivership.

Horse racing started again at the fairgrounds in 1937 under the auspices of the West Virginia Jockey Club. Wheeling Downs was constructed at that time with private money. It was an immediate success until the war.

In 1945, Bill Lias bought the Downs at bankruptcy auction for $250,000. He invested half a million dollars to improve the track. It was beautiful. They called it “Little Churchhill Downs.” He had people paint the curbs and everything else. The painted it all green and white.

Lias had the track for 11 years, until June 12, 1957. They had a big fire in 1962 when James Edwards owned the track. The damage was estimated at $1.5 million. The track sat idle for five years. Edwards put in a system under the track to keep it from freezing so that he could run races in the wintertime. In 1967, Edwards spent $2 million on a renovation of the Downs, which included a new grandstand. The track reopened in 1967 to celebrate its 101st year as a racing facility. Edwards sold the track in 1970 and the new owner, Ogden Leisure, attempted an unsuccessful change to harness racing. They closed the track in 1975 and reopened in 1976 as a greyhound racing park.

And that’s when I lost interest in Wheeling Downs.

Big Bill

I’m sure everyone has heard of Bill Lias. He was probably the second biggest racketeer in the United Staes behind Al Capone. He lived at the McCoy Apartments (later the Alice Apartments) at 41-15th Street. At birth, he weighed 12.5 pounds and as an adult, he weighed 400 pounds. He used to average about 368. As an adult, hee stood 5’2 with a 66-inch waist. He used to drive a Cadillac and he had the steering column shortened and the seat moved back so he could fit in to drive it.

His father passed away when he was only three years old and he was raised by his mother. He controlled the rackets in Wheeling for over 50 years. He supplied the gambling, booze, and entertainment to the residents and visitors to Wheeling, and he made Wheeling Downs one of the finest half-mile tracks in the country.

He went to Center School and dropped out in the 6th Grade. People say he would have been a great businessman if he’d stayed in school. They said the same thing about Al Capone.

Lias’s brother owned a bakery and he started working there. When he got old enough to drive, he would go into Ohio because whiskey was legal there. He would bring whiskey back in kneaded bread. His brother got caught and Bill took the rap and served six months for his brother because his brother was married.

The police would allow anything “on the other side of the creek.” And that’s why prostitution flourished there at that time. It was so common. It was in neighborhoods down there where they would have these houses of ill repute. And the people that lived down there would buy signs and put them on their door so that people would know they weren’t houses of prostitution. “Beware of the Dog” and things like that. The funny thing was that in the summer time, the neighborhood kids would go to these establishments, and they’d give them candy and soda pop, and treat them like royalty. And at 3:30 when the shift changed in Benwood and Wheeling, they kicked the kids all out because there would be over 5000 workers there in those factories, and they would all go to town and [pause] before they went home to dinner.

Lias had numbers joints all over. In fact, you could buy a number in the city building, that’s how bad it was. Why was is so popular? Because you could bet a penny. And the odds were like 600 to 1. So, Bill Lias, where he made his money – if somebody bought a number and there was a lot of money on it to one bookie, he would lay off that part of that bet to Bill Lias and he would charge the guy because if that number hit it would wipe the guy out. So he did that for many, many bookies and that’s how he made all of his money. He himself didn’t even bother selling the numbers.

When that became illegal, he got into slot machines. And every place had slot machines. The Elks Club had slot machines. A big percentage of what the Elks made, they gave to the orphanages and different charities around Wheeling. And then the government came and closed those down.

There’s another story about a prominent attorney who went to Zellar’s Steak House when Lias owned it. The attorney was there with his wife for an anniversary celebration, and he had a lot of money on him. He lost all that money plus three or four IOUs that he had given to Zellars. The next morning, one of Lias’s men went to his office, gave him back all the money and the IOUs. And that’s how Lias got a lot of favors done in Wheeling.

When Lias bought Wheeling Downs, they only had enough ground at 113 acres to make a half-mile track. Most of the tracks had a dirt track and a turf track. Lias wanted to make it a mile track. And he went to the board of education and offered to build them a stadium on the Island of any size they wanted and to put it any place they wanted to have it. And they turned him down. Three times he tried to do that. But what he did with that half-mile track was remarkable. It brought a lot of people to Wheeling from places like Cleveland and Pittsburgh. He had some of the best horses there, and it was hard for the horses to run on a half-mile track because the turns were so sharp. And they were limited on the distances they could run. They’d run five furlongs, six and a half, and then up to a mile, mile and an eighth, or mile and a sixteenth. A furlong is two hundred twenty yards, or an eight of a mile. The bigger tracks could run longer races.

“The Downs is noted for its sparkle and cleanliness. It is one racing plant where, regardless of the weather, the visitor encounters no mud…Located in the heart of the teeming Upper Ohio Valley, served by the National Highway and other important arteries, an hour and a half by motor from the City of Pittsburgh, the Downs is a must for the discriminating vacationist who enjoys the sport of Thoroughbred racing at its best.”

-From the inside cover of a Wheeling Downs foldout postcard booklet, circa 1955.

Wheeling Downs under Lias was a like a small city, with its own police force, gardeners, doctors and nurses, and sanitation workers. It was one of the largest employers in the city. There were cashiers and sellers, and ushers, and people in the grandstands and stewards and patrol judges.

Lias had a hydraulic lift at the finish line, and he’d look down at the finish line. On the other side were the stewards and the officials, also on a large hydraulic lift.

You could see Big Bill, but you never got close to him. He ran his own horses over there, and that was when he was getting into some financial trouble, and people didn’t like that.

Over on the Island, it was very prosperous for people that lived over there, because they would rent rooms out to the jockeys and trainers and other track people. My grandmother had two of them stay with her. She lived on Ohio Street, and she had seven kids, so she had plenty of bedrooms.

|

|

Eventually, the federal government came after Lias. The interesting thing is, when he had his case before the federal government, Bobby Kennedy was the prosecuting attorney on it. They were trying to prove he wasn’t born in the United States but was born in Greece so they could deport him. But they lost the case.

Lias lost the track when he was later charged with income tax evasion. But the federal government lost money trying to run it, so they hired back Lias to run it. The president of the United States at that time made $100,000 per year. The secretary of state made $35,000. At the time, Lias was paying himself $65,000 to run Wheeling Downs, and he told the feds he would do it for $55,000. They settled on him getting $35,000, which made him the second highest paid federal employee in the United States.

Lias died on June 1, 1970. He lived in the apartment on 15th Street until his death.

They’re All Gonna Win

How I got to be involved with Wheeling Downs was, when I was about five or six years old, my dad always used to go over to the racetrack. He had the parking garage up on tenth street. People came from all over back then to go to the Downs. There was the Wheeling Hotel and right across the street was the Bridge Bar Hotel. It was a huge bar. People stayed at the hotel and naturally, they had to park their car somewhere, so they parked in my dad’s parking lot. Every once in awhile, they’d give him a tip. He would say, “Come on Hugh, we’re going over to the track and I’m gonna spend some more of my heir’s money today.”

They’d sit in the club house and he would take me, and I really liked it with the horses and all. And I’ll never forget one day, he wasn’t doing too well, and he said, “How about you pickin’ the horse in here?” I said, “You really want me to pick one?” He said, “Yeah.” So, I remember to this day, the horse’s name was “Big Sneeze” and it came in and it paid $10.60. And I said, “Boy, this is really good! Do you want me to pick another one?” And he said, “No. I’m gonna give you a bit of advice. He said, “You can beat a race, but you can’t beat the races.”

And one day, I proved that wrong. When I was the admissions director at Wheeling Downs, I was in charge of the people in the parking lot, the ushers and the gatemen and others. And there was a big outfit that came down from Canada, and they had horses. And they didn’t want to park in the regular place over there. And the guy that worked in that area told me, and I said, “That’s fine, put ‘em wherever they want to park.”

So, it was about two weeks later and I’ll never forget, the guy’s name was Mike Vassaro, and he said, “You know, we’ve never been to a football game in the United States. We’d like to see how different it is from the game we play in Canada.” So I said, “Sure. No problem. When do you wanna go? The high school plays over here on Friday nights.” He said, “Well, can you get us in?” I said, “Well sure.” I knew the guy that worked the pass gate in there. About another week later, Vassaro came up to me and he said, “Hugh, I’m gonna give you a tip. I’ve got seven horses running tonight (they only ran an eight race card back then). And they’re all gonna win.” And I said, “They’re all gonna win?” And he said, “Yeah I brought Al Whitman (that’s a jockey from up in Canada—he was one of the best up there).”

So, it was about two weeks later and I’ll never forget, the guy’s name was Mike Vassaro, and he said, “You know, we’ve never been to a football game in the United States. We’d like to see how different it is from the game we play in Canada.” So I said, “Sure. No problem. When do you wanna go? The high school plays over here on Friday nights.” He said, “Well, can you get us in?” I said, “Well sure.” I knew the guy that worked the pass gate in there. About another week later, Vassaro came up to me and he said, “Hugh, I’m gonna give you a tip. I’ve got seven horses running tonight (they only ran an eight race card back then). And they’re all gonna win.” And I said, “They’re all gonna win?” And he said, “Yeah I brought Al Whitman (that’s a jockey from up in Canada—he was one of the best up there).”

By the way, my dad had four brothers. My Uncle Melvin worked as a cashier over there and the other three brothers, when they got done work, they all came over to the track. And I had two aunts: Thelma was a teacher at Ritchie School, and she was an old maid schoolteacher, and she came and she bet big, and she came over with my other Aunt, Betsy.

Anyhow, I had $125 in my pocket that night. I remember that distinctly. And the first race, I bet, I forget how much, and the horse won. The second race came and I bet a little bit more. That horse won. I thought my luck was gonna run out so I didn’t bet the next race. That horse also won. To make a long story short, all seven of them won. And my Aunt Thelma, who I kept giving the horses to, like I said, she bet big. Well she had money in her purse and it was popping out. And her raincoat pockets were full. She lived in Warwood and I said, “Thelma, I’m gonna call a cab to get you home. You’ll never make it this way.” And I said to myself, “Boy this is my night. I think I had close to $3000 in my pocket.”

So I thought, “Well I’m going down to the Pirate Café – they had a barbooth game down there. It’s a dice game. It’s the only legitimate, fair game, because you bet against somebody else. All the house does is take the rake off and count how much money’s been bet. To win you threw two twos, or two threes, or a two-three. When you lost you threw two sixes, two fives, or a six-five. Anything in between, you didn’t owe anything. In 45 minutes, my three thousand bucks was gone. I was down to my $125, and I went home and my dad said, “How did you do?” And I said, “Well I broke even for the night.”

I Saw a Lot of Things Happen

I saw a lot of things happen at Wheeling Downs. I saw one jockey jump off his horse at the finish line—his name was Carillo. I saw him pull another jockey off his horse and they had a fist fight right there on the track underneath the finish line.

My dad bought two horses. Well actually, he paid the feed bill for the guy that had the two horses. He was in financial trouble so my dad did him a favor. The names were “Thunder Lee” and “Walmiss.” [In the program below from 1940, Mr. Stobbs jokingly listed his wife as the owner of Walmiss because of her disapproval of his race horse ownership.]

At that time, black jockeys hardly ever got to ride. There’s was a lot of racism back then. But there was a little guy, I’ll never forget. He couldn’t have weighed more than 90 lbs. His name was Hubert McKinney. What they did let him do over there was exercise the horses in the mornings. And he came up to my dad and he said, “Mr. Stobbs, I’d give anything if you’d let me ride one of your horses.” My dad said, “Sure.” And he let him ride. Well, he won the race on the first horse. So he was pretty good. He ran a lot of races for my dad. One year on Thanksgiving, my dad got a telephone call, and it was from Hubert McKinney in Charlestown. And he said, “Mr. Stobbs, I’m going to return the favor you did for me. I’m riding today and they’re putting ‘Black 99’ up on the board.” And that meant, that was as high as the odds could go. And so it had to pay $200 at least. And the black referred to his color. Anyhow, the horse did come in and it paid, I think it was $260.

I started out in the parking lot on South Broadway, collecting 50 cents on the cars. They charged that and then they charged an admission to get in. After the sixth race, you could get in for nothing. And people would line up before the sixth race. When I was in charge of the pass gate where you came in, some of Hubert McKinney’s friends came in and I took them up through the pass gate, and they appreciated that.

I started out in the parking lot on South Broadway, collecting 50 cents on the cars. They charged that and then they charged an admission to get in. After the sixth race, you could get in for nothing. And people would line up before the sixth race. When I was in charge of the pass gate where you came in, some of Hubert McKinney’s friends came in and I took them up through the pass gate, and they appreciated that.

They had some really first class horses at the Downs. Three of the best jockeys at that time were Ray Bellinger, Francisco Salmel, and Forrest Kaelin. Forrest Kaelin was what they called an apprentice jockey. They were also called a “bug boy,” because they put an asterisk behind their name when they listed them in the programs. You got a ten-pound allowance weight back then, so if you were an apprentice, if the horse carried 118 lbs, it only had to carry 108. So they got a lot of preference that way. But as soon as you won five races, that weight dropped to five pounds. And then by the time you either won 40 races of the year was over, you lost your apprenticeship. Forrest Kaelin is still a trainer down at Ellis Park, and he went to the big tracks to ride later on. He was the leading rider for one or two years. He was good.

Bill Hogan was what they called the “runner” over there at the track. And what the runners did (they didn’t have computers like they do now), they had to give you a ticket. So the sellers were here and the cashiers were down here. And if somebody gave them a twenty dollar bill for a two dollar ticket, the seller would holler, “Change!” and the runner would get the change. If the cashier wanted to but a ticket, Bill would take his money and buy a ticket. If it won, he would get a small amount to run the winnings. So he ran back and forth cashing and selling tickets for the people that worked there, which was a pretty good deal.

It was tough being a cashier, because they had different codes on the tickets, and if someone handed you four or five tickets on race number five, you had to look at that code and make sure it was the right ticket. You had to make sure all five tickets were right. Plus, if it was $5.60, you had to figure up what you had to pay out, using your own multiplication. And they didn’t have all the exotic betting that you have now. Over there you could only bet a Daily Double, which was the first and second race—you picked the winners of the first and second race. And it paid more than a regular ticket. All they had was win, place, and show. They didn’t have all the exactas and things that they have now where you have to pick first and second place, or a trifecta, where you have to pick first, second, and third, or superfecta, in which you pick one, two, three, four. They did have the quinella, and in that one you could pick one two and they could run one tow or two one.

It was tough being a cashier, because they had different codes on the tickets, and if someone handed you four or five tickets on race number five, you had to look at that code and make sure it was the right ticket. You had to make sure all five tickets were right. Plus, if it was $5.60, you had to figure up what you had to pay out, using your own multiplication. And they didn’t have all the exotic betting that you have now. Over there you could only bet a Daily Double, which was the first and second race—you picked the winners of the first and second race. And it paid more than a regular ticket. All they had was win, place, and show. They didn’t have all the exactas and things that they have now where you have to pick first and second place, or a trifecta, where you have to pick first, second, and third, or superfecta, in which you pick one, two, three, four. They did have the quinella, and in that one you could pick one two and they could run one tow or two one.

Back then, almost everybody wore the spade shoes. They were shaped like the spade on a playing card. And there were people called “skimmers” and they would file the inside of their shoe down until it was razor thin and they could walk along and without missing a step slip tickets over it, looking for people that had thrown away good tickets. That happened frequently because if someone bought a place ticket and the horse would win, they thought they had to run second for them to win. And skimmers made a lot of money that way.

Back then, the jockeys were required to weigh a lot less than they are now. When they asked one of the leading jockeys in the country, Jerry Bailey, what he was going to have for lunch, he said, “A peanut.”

And some of the jockeys, to get their weight down, would get in a rubber suit or a plastic suit and get in the horse dung, to get the heat, so they could lose weight. When Bill Lias renovated Wheeling Downs, he told his contractor he wanted a sweat room for the jockeys put up at the top of the administrative offices.

One time, when I as a kid, it was a Sunday morning, I’ll never forget. Where the parking lot is now, that was where all the stables were and they had trailers parked in there. And I heard this loud bang and I wondered what happened. It turned out a jockey’s wife had shot him in the trailer with a double-barreled shogun. It cut him in half.

My mother never went over to the races. She really didn’t care for it. And when my dad got the two horses, he needed a jockey shirt. And he got my mother to make that jockey shirt. I thought there was going to be a divorce. But I’ll never forget: it was purple and gold with a big S on the back of it. I wish I had it. I don’t know whatever happened to it.

I worked there even after Bill Lias lost the track. My boss then was a fella named Maurice Brown. He was out of Detrioit. I didn’t know how to read him. Anyhow, I worked over there about twelve, thirteen years and I really enjoyed it.

So that’s all I can tell you about Wheeling Downs and Big Bill Lias.

Wheeling Downs Timeline

Pieces from Mr. Stobbs’s extensive collection of Wheeling Downs memorabilia are currently on display in the store windows at 1310 Market Street in downtown Wheeling and in the main display area at the library. The exhibits were designed and curated by the Ohio County Public Library Archives and funded by Wheeling Heritage. The displays feature photographic enlargements by McClellan Sign Company.

Sprint car racing was held at the Downs in the 1930’s for about 4 years. I have some pics.